Author

Director, Institute for Screen Industries Research and Associate Professor of Film and Television, University of Nottingham

Disclosure statement

Gianluca Sergi does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

University of Nottingham provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

- Email

- Twitter

- Facebook

- LinkedIn

- WhatsApp

- Messenger

The UK cinema association announced late in 2018 that movie admissions were on course to hit 176m for the year, 6m more than in 2017 and the highest since the 1970s when blockbusters such as Star Wars and Jaws had people queuing round the block. This in an era of streaming, online sharing platforms and on-demand, on-the-go access to virtually any film, anywhere.

Against increasingly tougher odds, cinema-going remains the most popular form of cultural participation and public social engagement – and it is the same story pretty much wherever you look around the world.

Behind this success story, though, lies a serious threat. Despite billions of tickets sold every year worldwide and box office revenue steadily increasing since the 1970s (reaching over US$40 billion in 2018) these numbers mask a gradual narrowing of the socioeconomic spectrum of cinema-going audiences.

If the trend of increasing ticket prices and the business models that underpin this increase continue, this staple form of public participation and communal engagement will lose its social function. Rising ticket prices will effectively exclude many of those for whom cinema was intended in the first place, resulting in its complete gentrification.

Rising prices

As part of my research, I calculated the relative cost of movie tickets over the years and compared that with wages. It paints a bleak picture. Adjusted for inflation to give a contemporary perspective, attending a movie theatre in 1938 in the US (the year the Fair Labor Standards Act established the federal minimum hourly wage) cost the equivalent of US$4.14 (calculated by adjusting the original ticket price to January 2019 prices.

That meant that for every hour worked at minimum wage – then set at US$5.39 – film-goers would invest roughly 75% of one hour’s work. In 2018, going to the cinema cost US$9.11 – so a minimum wage worker would need to invest 125% of their hourly wage to buy a cinema ticket. US minimum hourly wage has been stuck at US$7.25 since 2009.

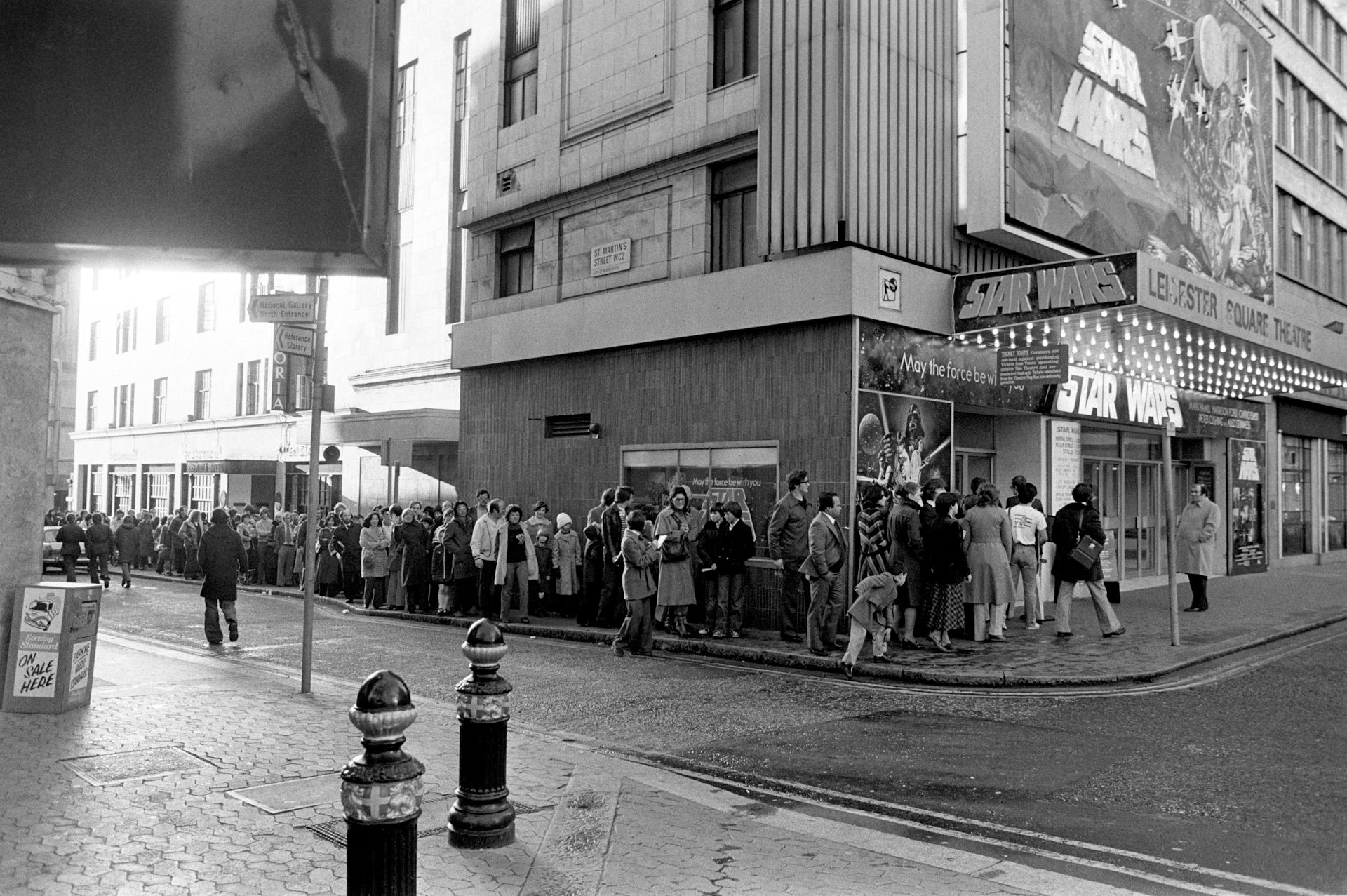

Cinema-goers queue outside the Leicester Square Theatre for the London opening of the movie Star Wars in 1977. PA/PA Archive/PA Images

Cinema-goers queue outside the Leicester Square Theatre for the London opening of the movie Star Wars in 1977. PA/PA Archive/PA Images

In the UK, the situation is only marginally better. Cinema prices average £7.22 (US$9.40) against a minimum wage set at £7.83 (US$10.20) for over-25s – but dropping rapidly for those below that age to as low as £5.90 (US$7.70) for 18- to 20-year-olds.

Why does this matter? At a time when few places offer everyone in society the opportunity to access a shared human experience – to laugh and cry at the same things in the same shared space – it is of paramount importance that cinema remains affordable to all.

Social significance

It is not a matter of cultural significance but of social significance. When Steven Spielberg says that “there’s nothing like going to a big dark theatre with people you’ve never met before and having the experience wash over you”, he’s not making an argument about the superior artistic stature of cinema – to prioritise one art form over another is absurd.

Filmmakers like Spielberg remind us that going to the cinema has, over the course of the past century, become a right of everybody to participate in the cultural life of the nation.

Historically, cinema achieved this crucial role as a cultural and social meeting-point by being affordable to all – ensuring that the most diverse cross-section of the population could afford to go to the cinema regularly. In this sense, it is fundamentally different to television or video games, because going to the cinema is a cultural practice that requires a social contract between the audience, the exhibitors and the filmmakers – where you agree to leave the house, sit in a dark theatre and share the film experience with people you don’t know.

This may sound strange, but seeing a movie and going to the cinema are two different things. Going to the cinema requires a level of commitment that is fundamentally different to choosing to sit down and watch television or play with a games console at home.

London 1941: people queue to see The Philadelphia Story and Gone With the Wind. Imperial War Museum

London 1941: people queue to see The Philadelphia Story and Gone With the Wind. Imperial War Museum

It’s not about the artistic quality of the medium – but of democratic participation and the consequences of increasing levels of division in society. At its core, film is proven to have a shared emotional, artistic experience – not just with friends, but with strangers and, crucially, in a public space which, at least for those two hours, belongs to everyone.

For the many

While there is no easy fix to this issue, sliding price scales based on income and other related factors, to name one particularly intriguing way of rethinking prices that has already proved to be successful where trialled, may provide a useful starting point for the conversation.

This is a tale with no obvious villain – cinema owners invest huge amounts of money every year in upgrades while studios spend many millions making the movies they believe people want to see. For this story to have a happy ending it is therefore crucial to ensure that the conversation does not get stuck in the kind of simplifications (film versus Netflix, distributors versus audiences) that may make for good headlines but mask the real risks we all run if cinema should become a pastime for the few.

So ensuring access to the cinema experience for everyone should be part of the political and social conversation – not just an issue of preference. Streaming is not the enemy in this picture, but allowing significant cross-sections of the cinema-going population to be cut off from the most popular form of cultural engagement, most definitely is.