Author

Professor of Cultural Policy Studies, Murdoch University

Disclosure statement

Toby Miller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Partners

Murdoch University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

- Email

- Twitter

- Facebook

- LinkedIn

- WhatsApp

- Messenger

Ian Thorpe is unpopular with some critics, despite a largely positive reaction when he came out last weekend. The issue is money.

Stories are circulating that he was warned prior to the 2000 Olympic Games about the financial impact on the Canadian swimmer Mark Tewksbury, who came out in 1998 (six years after he won gold at 1992 Olympics) and lost a “six-figure speaking contract”. So Thorpe stayed where he was.

When Thorpe resumed training in the hope of selection for the 2012 Olympics, his fellow swimmers allegedly demanded their governing body reveal the payment involved in this comeback amid rumours of “six-figure handshakes”.

Swimming Australia was in a tight spot, with ratings drooping and prime-time TV coverage imperilled. So if payments were made, they were presumably an investment in star power to regain media attention and boost revenues.

Much of the frenzy surrounding last Sunday’s television interview with Michael Parkinson has also been to do with dollars as Ten Network, who screened it, apparently agreed to hire Thorpe as a commentator on the Commonwealth Games as a quid pro quo

So how badly has Thorpe jeopardised sponsorship opportunities with his coming-out announcement?

The stakes are considerable. By 2005, US celebrity endorsements amounted to over a billion dollars. Such investments are predicated on the assumption that audiences imagine they can magically transfer star qualities onto themselves by purchasing commodities associated with their idols, from shoes to supplements.

Inevitably, though, things go wrong with a system based on tests of desire, denial and physicality. There is an almost taken-for-granted oscillation between athletes’ good and bad conduct: high-performance dietary supplements versus illegal drugs, sexual display in advertisements as opposed to extra-marital affairs in private, club loyalty and disloyalty.

Because the body is the currency of sport, its passions and unreliability mark it out for disappointment and excess as much as fulfilment and success. And bodies become old, creaky and uncompetitive.

We know almost too much about sporting celebrities, most notably what their bodies look like in extremis

Sexuality in the pool

Thorpe’s situation intersects with the historic identification of swimming with homoeroticism, as per English artist Duncan Grant’s famous 1911 painting Bathing, which shows young men frolicking naked in the waters.

Swimming is regarded as masculine because of its self-sufficiency and demands for fitness, strength, and skill. But the sport’s lack of violence marks it out from body-contact games.

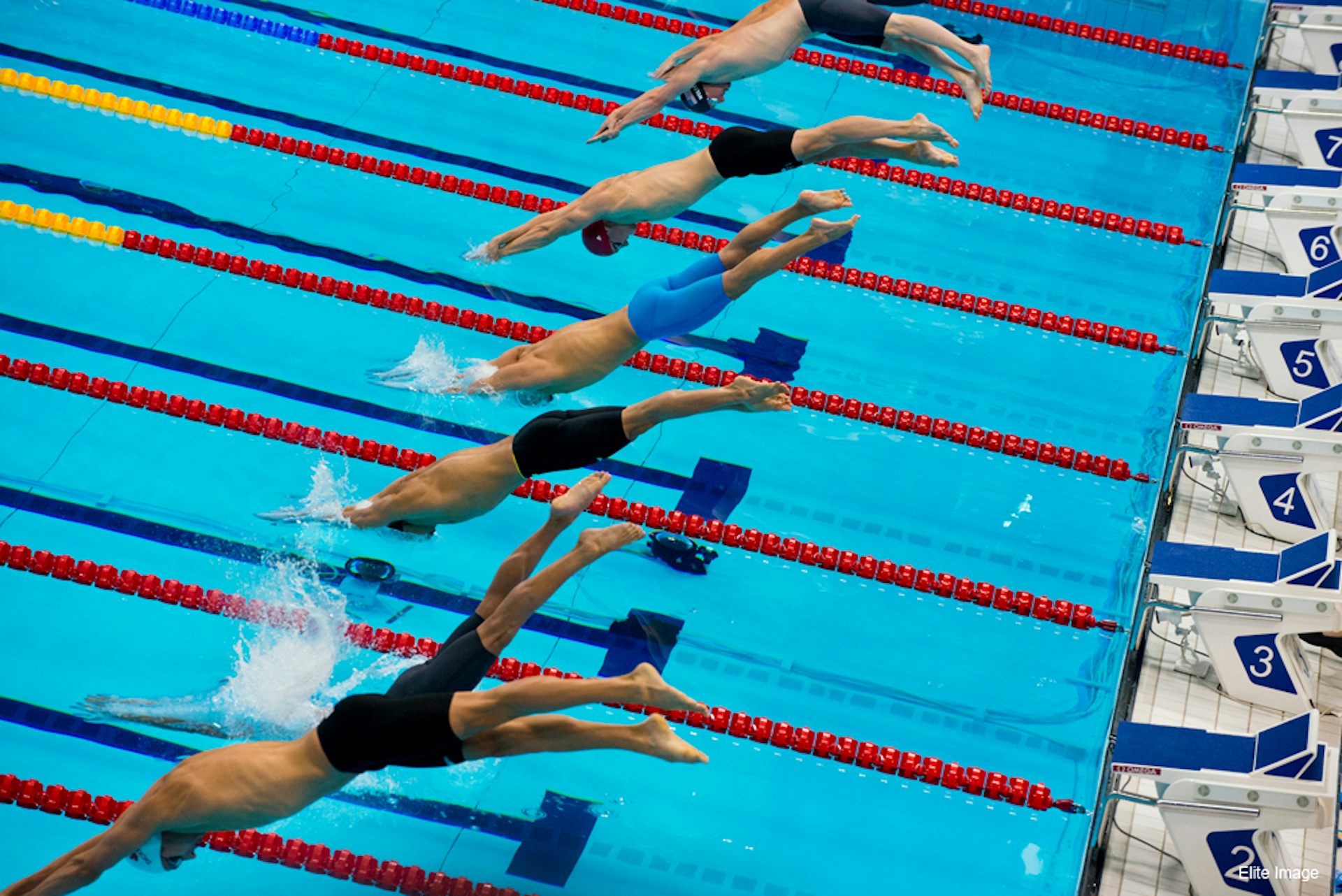

Olympic swimmers diving into the pool in London, 2012. Atos

Olympic swimmers diving into the pool in London, 2012. Atos

Elite male swimmers are outlined in form-hugging briefs or bodysuits, hair trimmed for minimal drag, lean, leggy, ducking, diving, turning, and speeding, seemingly oblivious to the gaze of others and the actions of fellow-competitors. Bug-eyed in goggles, their muscles strain with each eruption from the water.

The uncomfortable sense of the male body straining while almost naked can lead to some interesting practices of compensation in the media.

In the past, the BBC has seen the perils to conventional masculinity incipient here: instructions to its camera operators for the 1976 Games emphasised the need to capture swimmers’ “straight lines” in order to suggest “strength, security, vitality and manliness” rather than the “grace and sweetness” of “curved lines”.

And gay men in the pool?

Greg Louganis (right) with his companion arrive to the AIDS Solidarity Gala in Vienna, Austria, 2013. EPA/ Georg Hochmuth

Greg Louganis (right) with his companion arrive to the AIDS Solidarity Gala in Vienna, Austria, 2013. EPA/ Georg Hochmuth

American Bruce Hayes, an “out” swimmer who won relay gold at the 1984 Olympics, was a key figure in Levi Strauss’ 1998-99 dockers campaign. The champion diver Greg Louganis did not lose support from Speedo or other sponsors when he came out.

Just this week, prompted by Thorpe’s interview, the ASB Bank in New Zealand announced that its sponsorship contracts will all now guarantee diversity.

But the issue of sexuality and sponsors is multi-sided. This year’s Sochi Winter Games faced controversy because of host country Russia’s ban on public discussion of gay rights. Human Rights Watch and many other non-government organisations, such as Amnesty International and the Russian LGBT Network, wrote a letter of complaint to the ten key Olympic sponsors, most of whom met with them.

But with over 80% of Russians supposedly in favour of the law, this presented difficulties to corporations that saw a large emergent consumer market and felt overwhelming greed.

So Thorpe, the closet, and money have quite a history. Their future may be much shorter. Part of that — an end to secrecy — he will no doubt welcome. The other part — financial uncertainty — he may not. But ultimately, sponsorship issues could arise from Thorpe being yesterday’s hero rather than being gay.